“Ubi caritas et amor, Deus ibi est.” Before there was a formal Catholic Mass structure, this hymn galvanized the early Christian community based upon its core belief. What is that core belief? The Latin text is usually translated as, “Where charity and love are, God is there.” Thus, if people wish to bring about God’s kingdom, it would seem charity must abound. So, let’s reflect upon what constitutes “charity.”

The English word “charity” derives from the Latin word “caritas” but there are some important nuances that seem to be lost in translation and perhaps in practice. “Charity” means to voluntarily give to those in need whereas “caritas” means “dearness”, “esteem”, “high-priced”, “costly”, “fondness”, “attachment”, and “affection” in addition to “charity”. There is a sense of value-related connection associated with the Latin word “caritas” that is lost in our modern translation to “charity.” For many people in today’s world, charity seems to be detached but caritas was very personal and connected.

In the early church, when caritas carried its fuller, richer meaning, all community members gave of themselves to the rest of the community.

The community of believers was of one heart and mind, and no one claimed that any of his possessions was his own, but they had everything in common. With great power the apostles bore witness to the resurrection of the Lord Jesus, and great favor was accorded them all. There was no needy person among them, for those who owned property or houses would sell them, bring the proceeds of the sale, and put them at the feet of the apostles, and they were distributed to each according to need (Acts 4:32-35).

“From each according to ability to each according to need” is one way to summarize this passage from the Acts of the Apostles. It was the philosophy of the community but it was a lived philosophy versus an empty phrase hanging on a plaque. Consequently, the early Christian church grew, not because people were emotionally flogged into abstaining from birth control, but because the marginalized knew that they had a safety net in a caring community where their basic personal needs would be addressed. And the privileged knew they had a safety net in a caring community, should their fortunes reverse or their popularity diminish. Instead of merchandising and profiting from their Christianity, they used the proceeds from their secular work to care, personally care, for the community and its members.

I fast forward to today. The Catholic bishops’ charitable organization is called “Caritas Internationalis” with national chapter affiliates such as Catholic Charities USA. However, what is the U.S. bishops’ personal investment in caring for others? About two-thirds of Catholic Charities’ funding in the U.S. comes from the government and the remainder from private donations. The bishops take a lot of money from taxpayers, enshroud it in their rules, and direct employees and volunteers to re-distribute it to those of whom the bishops approve. Rarely does a bishop have a personal role in any of these interactions: understanding the need, consoling those in need, helping those in need. Of late some bishops and their fan base have marketed the bishops’ charity organization’s works as part of a public relations effort to boost the bishops’ public image. Would this qualify as the caritas that defined and galvanized the early Christian community?

The bishops are not alone in offering detached charity. We must examine our own charitable efforts. Are they detached and impersonal efforts or do they more represent the full meaning of caritas?

One way to begin this reflection is to think of the motivation for doing charitable works. When such works are true caritas, it is all about doing the right thing because “those unfortunate people” are no longer “them” but “us”. They are “my” people. Thus the charitable acts are not about making me feel good or my tax write-off but about personally caring for people because God entrusts the care of humanity to all of humanity. At this point, such works occur because it is one’s honor or duty. There is not a sense of superiority as though “I am more fortunate and they are less fortunate.” At this point a person no longer helps other people’s children but instead treats those children as they would their own.

I once encountered a university chaplain who refused to help Libyan students facing deportation. The Arab Spring uprisings of 2011 froze these students’ scholarship money, preventing them from attending university and ultimately nullifying their U.S. visas. Returning to Libya meant almost certain death for these students. However, this chaplain explained that he was “too busy preparing for Lent and the alternate Spring Break mission trip.”

I also once encountered someone who repeatedly effused about a mission trip which she found “so cool” because she got to see and help so many “quaint poor people.”

Caritas is not a destination adventure. It is not a form of entertainment. It is not a form of sight-seeing. It is not to make you feel good. Should a person feel good that the misfortune of others gives them an opportunity to be helpful and generous? Or, should the vastness of opportunities grieve them, inspiring them to do as much as they can to help people, and fix broken systems that cause the volume of misfortune?

Many Catholics give to their local parish as an act of charity. Though churches legally qualify as charitable organizations in the U.S., the typical parish budget does not include funds for the needy. That is left to a separately funded and run group such as the St. Vincent de Paul Society. Most parish budgets allocate around a third to a half of collected monies to pay for the Catholic school, subsidizing the tuition of students regardless of financial need. Indeed, in most parishes to which I’ve belonged, the poor cannot afford to send their children to Catholic school, but still contribute to the weekly parish collection, unaware that this money will help pay the tuition of wealthier people.

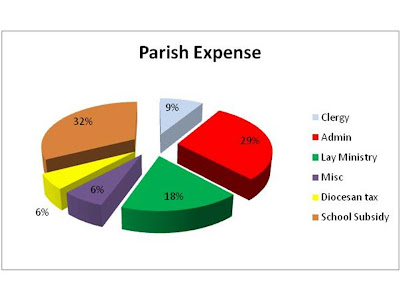

Here’s a representative hypothetical breakdown of parish allocations derived from consultative work I’ve done for a handful of parishes:

Most of the funding goes towards salaries and subsidizing school tuition. So, do charitable donations to one’s parish qualify as acts of caritas?

Finally, charity is about helping those in need. That requires defining “need” and “help.” Are these defined from the eyes of the person in need or by the person doing charitable works? When it is true caritas, it is from the eyes of the one in need.

I offer this example. Once after I was newly divorced, someone anonymously left bags of clothing on my doorstep. The clothing was really rags so they weren’t helpful. Furthermore, because I had a good job, I didn’t have a need. I was actually financially secure enough to be funding a scholarship for other children at the Catholic school my children attended. But, the incident gave me pause to wonder if the person who did that “charitable” act glowed euphorically for even a moment because they felt they had “helped” someone in “need.” If so, that was an illusion existing in their mind rather than in reality.

Is your giving about you or is it about others? Is it personal and connected or impersonal and detached? Do you perform works of charity or works of caritas?

By the way, the oldest version of the hymn had one additional word, “Ubi caritas est vera, Deus ibi est." And translated, that means, “Where there is true charity, there God is.” May we see an increase in true charity so as to experience an increase in the presence of God.

We've corporatized Matthew 25. But, so what? We've done that with everything else as well.

ReplyDeleteNot knowing you, Jono1, perhaps you are agreeing through sarcasm with the author of this post. However, if your question is sincere I find it distressing. To me, the point of Matthew 25 and of this blog posting is not that we need to give more MONEY, it's that we need to give more of OURSELVES. If we detach ourselves from acts of charity and see problems simply as something to throw money at in order to solve, I think we completely miss the human interactions component of the problems. You can donate millions of dollars to charity and still be the character who buried his money in the MT 25 story. Heaven is not about who makes the most money for God; this is a parable. Heaven is about LOVE and increasing relationships and self sacrifice for the good of the community. It's about investing an hour of your time to sit and talk with someone who is ill or homeless or in prison or grieving or depressed or stressed or confused or afraid. It's about the benefit to both of you from the time you share, not your own self worth or the monetary value of the transaction.

ReplyDeleteIf we 'corporatize" charity by making it easier to meet others from our community and share their troubles and more efficiently demonstrate our love, then I'm wholeheartedly supportive. There are institutions organizing volunteers and making it easier to get involved and matching people's strengths with others' weaknesses. But if we "corporatize" charity by turning it into a monetary transaction so we blindly remove ourselves from others' troubles, this is what I find distressing - perhaps most because this is what's easiest to do and so even I have done it. The challenge is to do what's hard, not what's easy.

~AMW